Citigroup’s announcement on Monday that it plans to stress finance and investing know-how in filling upcoming openings on its board of directors could be the tip of an iceberg.

More financial-services companies whose earnings were hijacked by their investments in subprime mortgage-backed securities and other kinds of companies simply struggling with the current economic downturn are likely to adopt the same strategy, according to some who are familiar with the workings of corporate boards. But that doesn’t necessarily mean the strategy is a sound one.

Citigroup stated on its website that it is “actively seeking new directors” and is placing a “particular emphasis on expertise in finance and investments.” As to its reasons, the notice said only that the move is “in response to shareholder inquiries related to the scheduled retirement of certain directors.” A company spokesman declined further comment.

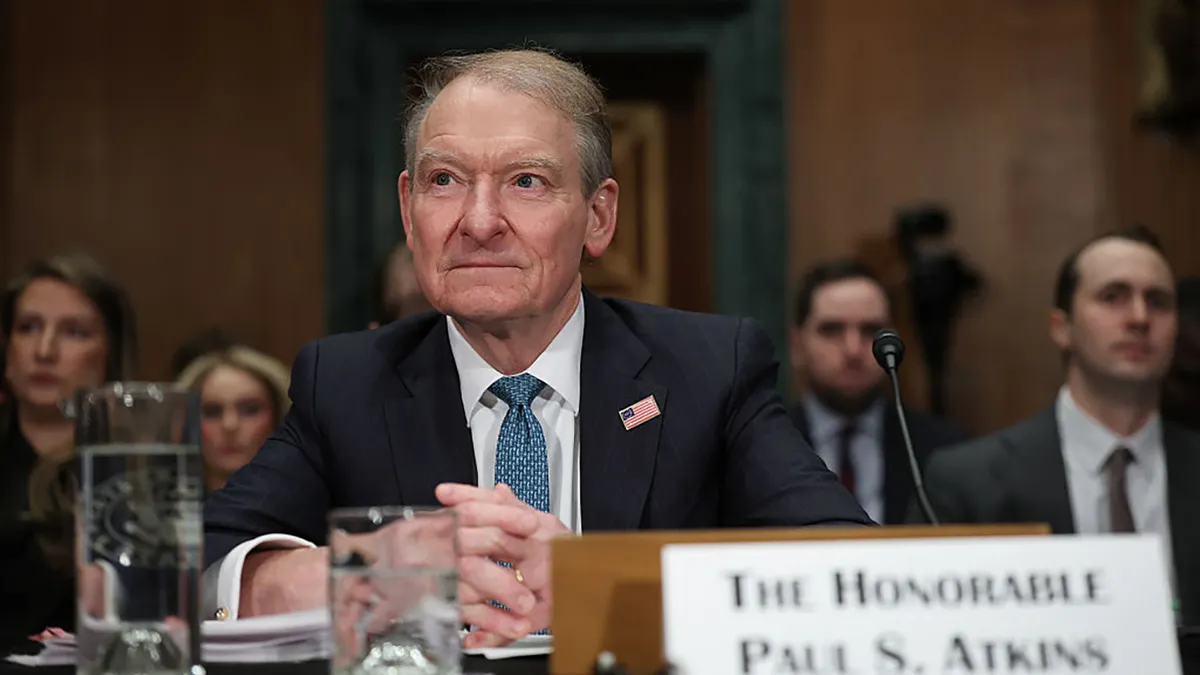

The Securities and Exchange Commission requires public companies to disclose whether they have at least one audit committee member with expertise in generally accepted accounting principles, financial statements, and internal controls, and if they do not, to explain why. At Citigroup, retired Medtronic CFO Robert Ryan is on the audit committee. Also on the board is Richard Parsons, chairman of Time Warner, who ran a New York thrift in the 1990s. Former treasury secretary Robert Rubin, the chairman of the company’s executive committee, is an internal board member.

Companies in all businesses, not just financial services, can be expected to follow Citigroup’s lead. “The financial people will come to the fore now,” said Milan Moravec, chief executive officer of Moravec & Associates, a management consulting firm that provides expertise on the makeup of boards. “Hopefully they’ll provide a better understanding of the direction companies need to go.” The operative word, though, was “hopefully.” Moravec told CFO.com that he doesn’t really expect such decisions to have much impact. He called Citigroup’s announcement “a knee-jerk reaction.”

Loading a board with financial people, even at a financial-services company, makes for a bad mix, according to Moravec. “You’ll have a bunch of technical experts who are not really very good at communicating with one another or at bringing about the right levels of constructive conflict and differences of opinion,” he said. “They’ll be likely to make the same kinds of poor decisions that were made before.”

Indeed, having too many finance experts could undermine one of a board’s chief functions, which is to ask “the dumb question,” according to Keith Hall, a former CFO of Lending Tree who now sits on three boards (public company, private company, and non-profit organization). Asking and answering such questions could have insulated companies from exposure to the subprime mortgage meltdown, he suggested.

Noting that he wasn’t singling out Citigroup and that he wasn’t familiar with what its board was doing, Hall told CFO.com, “If a board had an environment supportive of members asking dumb questions, they might have asked, ‘What are all these alphabet soup-like things like CDOs? How do they really work?’ If you had probed further, could it have been revealed whether there was proper documentation of the underlying instruments supporting these mortgages? Perhaps the most important dumb question would be, ‘What were the facts behind these subprime loans?'”

A different point of view was offered by Ramon Weil, a professor of accounting in the University of Chicago’s graduate business school who has done research on the roles of finance executives on corporate boards. He said Citigroup’s strategy is appropriate because it’s a financial services company. At a manufacturing company, say, someone whose expertise is largely in finance rather than in manufacturing might not have much to offer as a member of the general board.

Theoretically such a person is needed for the audit committee, but Weil pointed to problems there as well. “The most surprising thing in my research has been how many CFOs don’t know diddly-squat about accounting,” he said. “I’m suspect of CFOs on boards who have never been involved with accounting. They know about financial markets, earnings reports, borrowing, and dividend policy, but they tend not to be real helpful on audit committees about the kinds of accounting issues that have gotten so many companies in trouble.”

Yet that kind of CFO might be just the one that corporations are looking to install on their boards, according to Tom Kolder, president of finance-executive recruiting firm Crist Associates, for which placing board members is a key service.

In recent years, Kolder said, the catalyst for bringing CFOs into the boardroom was the new compliance demands brought about by Sarbanes-Oxley. Now, though, the trigger will be the devastating effects of companies’ risky behavior in the capital markets. That means a different kind of CFO will be in demand. “Whereas in the past coming up through the CPA track was the key qualifier, what you can expect to see now is treasury-related skills coming into favor,” he said.

Regardless, companies are ill-advised to view changing the board mix as a panacea for their problems, according to Hall. “I suppose the trend for more industry experts being put on boards [at financial services companies] will continue, but that doesn’t make a problem like the mortgage mess magically disappear,” he said. “It’s going to take a lot of work and time to sort matters out. Sometimes it takes a lot of dumb questions to get to the real answers. And let’s face it, there are a lot of guys on Wall Street who all thought they were doing the right thing and the risk wasn’t that great.”